Classical control: Transforms

Classical control methods simplify handling of a complex system by representing it in a different domain. The equations governing system dynamics are transformed into a different set of variables. A for a function $f(t)$ in the $t$ domain, an oft used transformation is of the form:

$$ \mathcal{T}(f(t)) = F(s) = \int_{Domain} f(t) \cdot g(s, t); dt $$

Mathematically, the integral removes the $t$ variable and only leaves $s$, thus converting from the $t$ domain to the $s$ domain.

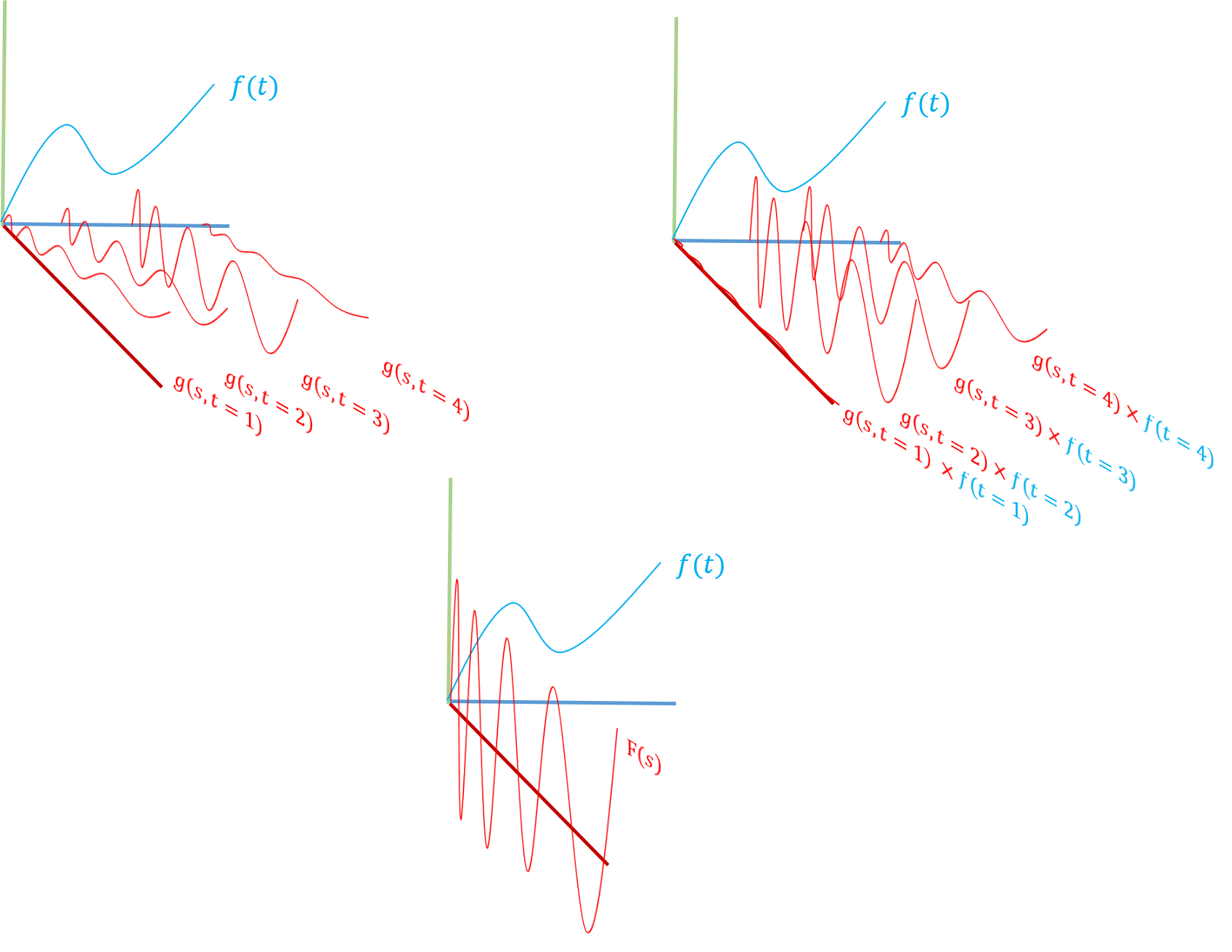

Along each point in the $t$-domain, the function in the $s$-domain $g(s, t=t)$ is scaled by the value of $f(t)$ at that point. The scaled curves $f(t=1) \cdot g(s,t=1), f(t=2) \cdot g(s,t=2)$ are all summed up leaving an aggregate function in $s$, $F(s)$ that is the sum of weighed contributions of $f(t)$. So if the original function was not in a palatable form, perhaps the transform - which encodes $f$ - may yeild a better representation.

Conceptually, a transform represents a function $f(t)$ in terms of combinations of curves of another class of functions $g(s,\cdot)$.

Theoretically, any class of functions can be used to transform from one domain to another (polynomials, square waves etc.). However, the utility of the transformation is in how meaningful the new representation is.

How a transform works. From top left, clockwise: $f(t)$ and the cross-domain function $g(s,t)$ evaluated at different $t$. Each of the $g(s,t)$ curves is multipled by the value of $f(t)$ at that point. Finally, the scaled curves are summed along the $t$ axis to leave a transformed function purely in $s$ domain.

Laplace Transform

The Laplace transform transforms a function into the domain of complex exponentials. More simply, it represents a function as a combination of different decaying sinusoids ($e^{-st}$) where $s$ is complex. The choice of decaying sinusoids reflects the physical systems whose equations are usually subject to the transform:

Transience: When a physical system is given input, like a spring which is extended, the response only lasts for a finite time. The stretched spring goes back to its original shape after some time. There is nothing about the string after it is restored that suggests that it was at one time stretched. The response to input is transient i.e. it decays. So functions that decay back to zero after a while will be able to represent the physical system well.

Periodicity: When a system is disturbed - the response is oscillatory. For example, when a pendulum is displaced it doesn’t go back straight to its initial position. Instead, it swings the other way, and then back several times. Therefore functions which are periodic - which go to the same value over and over - can represent such physical systems.

Mathematically:

$$ \mathcal{L}(f(t)) = F(s) = \int_{0}^{\infty} f(t) \cdot e^{-st}; dt $$

Where

$$ s = \sigma + \iota \cdot \omega $$

So

$$ e^{-st} = e^{-\sigma t} \cdot e^{\iota \omega t} = e^{-\sigma t} \cdot (\cos{\omega t} + \iota \sin(\omega t)) $$

To make mathematical sense, the exponent cannot have any units (e.g $kg$, $ms^{-1}$). And usually, the function to be transformed is in the time domain. Therefore the exponent $st$ must be unitless, and so the units of $s$ variable are $second^{-1}$ i.e. frequency. In control systems parlance, a Laplace transform converts a system equation from the time domain to the frequency domain.

Inverse Laplace transform

The inverse transform is given by:

Where $s = \sigma + \iota \omega$ is the complex frequency variable.

Fourier transform

The Fourier transform converts a function into the domain of complex exponentials as well. However, in this case there is no decay. So the real part of the complex variable, which causes the sinusoid to decay, is zero. Fourier transform is ideal for systems with a periodic - but not decaying - dynamics. For example, a pendulum with no friction or a spring mass system without gravity where there is no resistive force to take a system back to its rest state.

Mathematically:

$$ \mathcal{F}(f(t)) = F(\iota \omega) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(t) \cdot e^{-\iota \omega t}; dt $$

So

$$ e^{-\iota \omega t} = \cos{\omega t} + \iota \sin(\omega t) $$

Since Fourier transforms are based on non-transient functions, they are popular in domains like information systems and signal processing. They can be used to transform non-decaying, and possibly repetitive/patterned information - like an audio snippet or pixels in a picture - into a combination of constituent frequencies.

Inverse Fourier transform

The inverse transform is given by:

Where $\iota \omega$ is the imaginary part of the complex frequency variable $s$.

Both Laplace and Fourier transforms are useful because of the properties of their basis functions. Exponentials are eigenfunctions of differential operators. This means that differentiating or integrating an exponential will just result in the same exponential multiplied by a constant.

$$ \frac{d}{ds} e^{ks} = k \cdot e^{ks} $$

For differential equations which have derivatives, and convolution operations which have integrals, a function expressed as exponentials becomes easy to deal with. This is an important consideration for classical control systems - which have both.