Gravitational Slingshots

Note: This article was originally published on astroibrahim on Apr 10, 2013.

I always wondered why doesn’t the sun slow space probes down when they are leaving the Earth for outer planets. Isn’t there a risk that the probe might change its trajectory and fall into the sun? There is. You see, the more distant the space probe gets from the Sun, the more potential energy it gains. However, energy must be conserved at all costs. Therefore the probe loses its Kinetic energy (and therefore its speed) in order to get away from the sun. It is the same as when you throw a rock up into the air.

But there comes a point, as with the rock, when the probe loses all of its kinetic energy. At that time it has reached as far away from the sun as it can. Yes, you could add thrusters to make sure the probe continues its journey. But the extra weight and inefficiency of propellants known to us make it an unsuitable alternative.

Enter the Gravitational Slingshot! Nature’s way of compensating us (very marginally) for all the millions of years we’ve been dragged through the mud in the name of evolution. Through this method, space probes go into a partial orbit around a planet and emerge on the other side with a greater velocity. “No!”, some might say, because it is a violation of conservation of energy. Intuitively it seems that way, but it is all a matter of relativity.

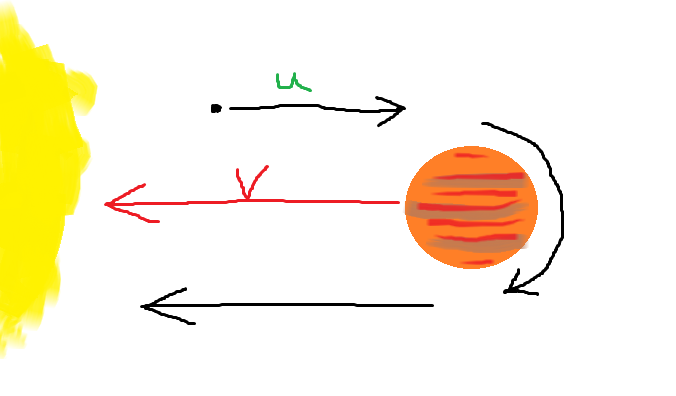

Imagine there is a probe approaching a planet with a velocity ‘u’. To an observer on the planet, the apparent velocity of the probe’s approach will be ‘V+u’, where ‘V’ is the planet’s and ‘u’ is the probe’s heliocentric velocity, i.e. velocity relative to the Sun. It will go into orbit at that speed. Now, when it comes out of orbit on the other side, it is still moving with a velocity ‘V+u’ relative to the planet’s surface. But the planet is also moving in the same direction at velocity ‘V’. So the final velocity as the probe leaves orbit will be ‘V+(V+u)’. Of course, some of that velocity will be reduced due to the planet’s potential, but in the end it will still be greater than the probe’s initial velocity.

If you look at what happened overall, ignoring how it happened, the probe approaches a moving planet at a certain velocity and “bounces off” at a higher velocity. It is just like when you throw a ball at the face of a moving train, the ball bounces off at a higher velocity. Now, the ball changes its momentum (first going in one direction, then another) and transfers that change to the train to ensure conservation. But the train is comparatively so massive that we do not notice the minuscule change in its velocity. That’s the same with planets and probes.

The effective increment in the probe’s velocity is due to the orbited body’s velocity relative to the Sun (analogously, the change in velocity of the rebounding ball depends on the train’s relative velocity to the ground). Of course, the Sun’s velocity relative to itself is zero. Therefore ‘V’ will be zero. So there will be no gravitational slingshot from the Sun (towards planets in its orbit) even though it is the most massive body in the solar system; just like there will be no increment in the velocity of the ball when you throw it at the ground.

≡

Ibrahim Ahmed